by Valentina Biondini, art and literature amateur

What is the definition of irony for a calamity visionary as I have been defined? Dying? Or worse, disappearing mysteriously in one of the military campaigns conducted during what was, in fact, one of the bloodiest calamities in human history, the Second World War? But let’s go in order. My name is Franz Sedlacek and, rightly or wrongly, I was one of the main Austrian artists active between the two world wars.

Born in Poland at the end of the nineteenth century, I had the opportunity to grow up and live in the prosperous city of Linz, in Austria. I worked as a chemist at the Technical Museum of my adopted city, where I later became director of the industrial chemistry department. At the same time, in my free time and as a self-taught person, I indulged my predilection for art, or rather my obstinacy to become a draftsman and painter. It was in this role, and while still very young, that I was one of the founders, together with Anton Lutz and Klemens Brosch, of the artists’ association Maerz in Linz and, a little later in life, I took part in the Viennese Secession, a group with which I shared the idea of creating original art forms not tied to the past.

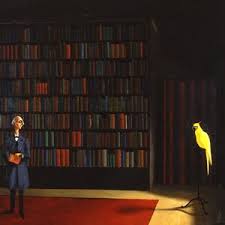

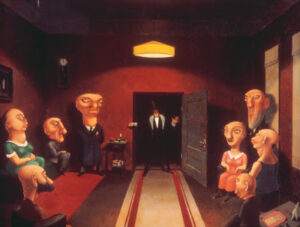

My work, full of mystery and charm, always seemed to be poised between childish joy and oppressive darkness. An anomalous painter like me was therefore difficult to classify, even if by convention I have been associated with the New Objectivity movement (Neue Sachlichkeit), a current similar to Italian magic realism and very close to surrealism. Yet, during my artistic career I have won several national and international awards. While in 1930 my paintings were exhibited at the MoMA. My paintings, so brilliant, unpredictable, characterized by an unusual irony, will seem to many in the times to come to anticipate a certain taste and a certain modern style, and even foreshadow the culture of street art and comics.

In fact, my works, populated by bizarre and caricatural beings, under the banner of the mysterious and the disturbing, have been ascribed to grotesque and fantastic art. However, the dreamlike and unreal nature of my first paintings contrasted forcefully with the clear, smooth and sharp contours of the subjects depicted in them. And it was precisely this contrast that had the ability to disturb the observer. All this does not surprise me because I must admit that I have always been fascinated by the disturbing, that I have always been attracted by that feeling of danger that Romanticism defined with the courtly term of sublime. After all, it doesn’t take much to arouse horror, it is enough to create fantastic figures at whose base are always forms of natural organs that proliferate or atrophy.

Later I turned to oil painting and turned my attention to the style of the old Swedish masters. My subjects shifted from ghostly dances and menacing atmospheres to vast and quieter desert vistas. These landscapes, although not entirely elegiac, exemplified my urge to depict themes related to the loneliness of the individual and human alienation.

In spite of myself, I was not only a chemist and a painter. I was also a soldier and, between the First and Second World War, I spent almost eight years of my life in the trenches. In 1939 I enlisted in the Wehrmacht, the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany. But try not to judge me too much for this, I had grown up in a nationalist and anti-Semitic environment that, by force of circumstances, had shaped and influenced me. My ideological involvement in Nazi propaganda, however, remains somewhat undefined. In fact, the codes of surrealism and symbolism that I used in my works allowed me to express, through subjects that passed from dream to nightmare, my anguished thoughts on the spreading situation, to tell my real experiences, without risking opposing the regime.

In the very last year of the war, 1945, in the same Polish land where I had been born years before, my tracks were lost. And that was how I disappeared, alone and alienated like the characters in my works suspended between dream and nightmare. My body was never found. But my visionary works are still visible at the Leopold Museum in Vienna.