by Valentina Biondini, art and literature amateur

My name is María Gutiérrez-Cueto y Blanchard, but you can simply call me Maria Blanchard and, although I am unknown to most, thanks to my talent I was one of the protagonists of the avant-garde.

I was born on March 6, 1881 in Santander in the north of Spain and my childhood was painful, in my body and spirit. In fact, I came into the world with a spinal malformation that forced me to walk with a cane since I was a child, which among my schoolmates earned me the unflattering nickname of bruja, that is witch.

Obstinate and stubborn as I was, I didn’t let the bullying (that’s what you call it today, don’t you?) from my peers get me down and I looked for a way to vent the anguish and sublimate the pain I felt. Encouraged by my father, Enrique Gutiérrez Cueto, journalist and man of letters, first I approached drawing and then painting. In 1903, at just over twenty years old, I entered the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando where I studied under the guidance of Manuel Benedito and Emilio Sala who taught me precision and that exuberant use of color that still today, according to many, constitute the characterizing elements of my first compositions. Precisely because of my use of green, black and brown tones, many art historians have traced a strong hispanic character in my works.

In 1908, thanks to a scholarship I was awarded with by the Municipality of Santander, (my poor father had died in the meantime and could no longer finance me) I was able to continue my artistic education at the Academie Vitti of Paris, under the teaching of Kees van Dongen. That first period in Paris was a true hotbed of experiences that marked me forever. From an artistic point of view I approached cubism. I also became part of the “Section d’Or”, an association of painters and art critics who identified with Orphism, a branch of Cubism. However, from a human point of view, I had the opportunity to meet some of the most extraordinary minds of the time, such as Jacques Lipchitz, André Lothe, but above all Diego Rivera with whom I fell in love with, even without ever declaring myself and, last but not least, Juan Gris.

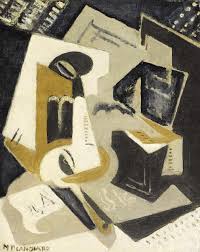

In 1914, at the outbreak of the First World War, I left Paris to return to the more secluded Madrid, to my mother’s house, where I set up a studio which I shared with some of the artists I had met in France. Some of my paintings belong to this period, such as “Donna con ventaglio” (1916), “Natura morta” (1917) and “Donna con chitarra” (1917), which well represent my intense study of the anatomy of things and the weight of color in my painting. In 1918, at the end of the war, after a disappointing experience as an art teacher in a school in Salamanca, I returned to Paris and I would never leave again. I decided to throw the surname Gutiérrez into the Seine and became once and for all just Marie Blanchard.

At the beginning of the 1920s I reached the peak of my career: I had the honor to take part in a series of exhibitions at the L’Effort Moderne gallery and at the Salon des Indépendants, where my work “Figure ou Intérieur” , known in Italian as “Il comunicante” received a great critical success. While in 1921 I exhibited my work at the Society of Independent Artists in New York. According to the critics, my second period in Paris coincided with a sort of “return to order”. I don’t know if this corresponds to reality. For me, the works of an artist are nothing more than the sum of experiences accumulated over the years. And yes, in fact, Cubism, which had been so important to me, had become too narrow. Therefore, returning to the figurative style was a natural transition, as well as getting closer to Cézanne’s constructivism. In fact, I felt that a more figurative, traditional style with strong contrasts between the bright colors and the melancholic themes portrayed was the closest to my personality.

However, my success proved to be ephemeral and although my name was known in the art world at this point , fame was not accompanied by the hoped earnings, also due to the economic crisis that was raging throughout Europe. Financially I began to depend on friends and patrons. Frank Flausch in particular was my biggest financier, until his death in 1926. But it was certainly not the economic problems and material deprivations that broke my spirit, but rather the premature death, at just forty years old, of my brotherly friend and workmate Juan Gris. If human feelings could be compared to the elements of nature, I would say that what I felt for Diego Rivera was fire, whose flames blaze high in the sky, but which in a short time reduce everything to ashes. While Juan Gris had been for me like the light that illuminates the day, with his death, therefore, I was plunged into the deepest darkness. It was then that I approached religion again, because it seemed like a torch capable of dispelling the darkness, and for a while I even thought about becoming a nun and lock myself in a convent.

In the meantime, however, my sister Carmen decided to come and live with me in Paris, bringing her children with her. Her closeness and that of my grandchildren had the effect of alleviating my sadness, so much so that I started painting again. Anyway, the serenity and artistic fervor regained were never accompanied by an increase in earnings. On the contrary, my finances languished further under the pressure of other mouths to feed besides mine. And as if that wasn’t enough, tuberculosis, that had afflicted me for a long time, flared up again, taking me away from art and leading me to death on April 5, 1932, at just 51 years of age.

My existence has not been stingy with pain, I grant you that. Yet if I can draw one lesson from it, and pass it on to you who read, it is that nothing made me feel alive like Art. Suffering, but pulsating with life.