by Valentina Biondini, art and literature amateur

The column “Who’s Next?” is renewed, not in substance, but in form. In fact, we will continue to write about unjustly forgotten protagonists of Italian art, culture and literature, but we will do it from another angle, that is, by narrating their story in first person, through a sort of fictional story or memoir, this time dedicated to the eclectic Rosa Rosà, writer, illustrator and futurist painter active above all in the 10s and 20s of the 20th century.

So let her voice guide us…

Just like Giorgina Rossi, the protagonist of my most famous novel, Una donna con tre anime, I too have experienced (at least) three different personalities in my long life. Of course, in my case, unlike Giorgina, it was not an improbable electromagnetic accident that triggered the psychic alterations, but more prosaically it was the unpredictable events of life that acted as a detonator between one and the other me. And, among these, without a doubt, the Great War must be counted. Yes, the war itself! The “only hygiene of the world” as defined by my futurist colleague Marinetti. But I hated it. And I wasn’t the only one: we women of the Florentine group of “L’Italia futurista”, of which I became a member, thought very differently from our male colleagues. Are you amazed? Well, what do I have to tell you? That’s right, get over it and go find out about the history books, assuming that you find any trace of us inside them. Which is actually very difficult, so I acquit you for lack of evidence.

I said, war, with all its trail of blood, violence, pain and death, was horrific to me. But, to tell the truth, there is a lesson that that filthy barbarism (other than world hygiene, puah!) has taught Italy and the whole world. That is, that women, in the absence of men called to the front, are able to run their own country. We rolled up our sleeves and succeeded in jobs that our fathers and husbands, not to mention our ruling class, didn’t think were right for our gender. But we have denied them all, as true and honest citizens that we are, and not angels of the hearth! And do you know why? Because we women are the backbone of society. And if the economy stood up it was only thanks to us, to our strength of mind, no less than that of our arms!

But let’s go back to the opening theme of this memoir, namely my three different personalities.

With the name of Edith Von Haynau I was a child born in 1884 in an aristocratic Viennese family. My education was entrusted to private tutors and mine was a terribly lonely childhood. My playmates were reading and my boundless imagination which saved me from the tedium of many hours spent alone. A little older, I carried out my first real personal rebellion: against the opinion of my family who considered artists as degenerates, I enrolled in the Vienna School of Art. But the best was yet to come: in 1907, during a cruise to the North Cape, I met a fascinating Italian writer, Ulrico Arnaldi. The following year we were already husband and wife and we had moved to live in Rome. Our four children were born here, as well as Edith Arnaldi, my second me. But war soon came upon our family as well as upon the others, and Ulrich was drafted into the army. I was tempted to give in to despair, but literature saved me again, just as it had saved me as a child. Therefore I decided that I would not let myself be engulfed by pain and worry. Or rather, I granted it only to a part of me: to Edith Arnaldi, the devoted wife and loving mother.

I decided to be reborn as Rosà, from the name of a Venetian town that I had visited some time before and that had struck me with its beauty. Thus was born the third me, the Artist and the Literate. And since I wanted to make my voice heard, I decided to double my name which became Rosa Rosà.

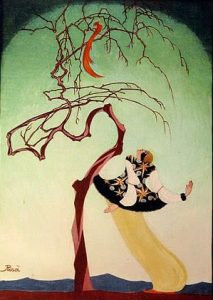

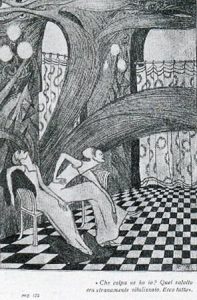

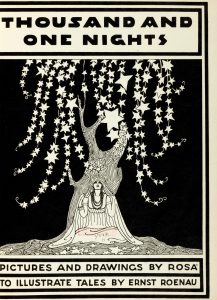

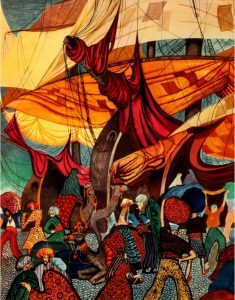

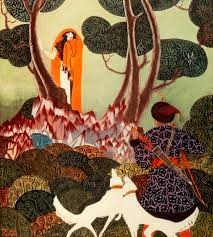

How much fun I had with Rosa! Although the privations of the war did not discount anyone, through her I was able to express myself as I had never done before. I approached futurist art with my drawings of futuristic cities and my paintings tending towards abstractionism, but also with ceramics, sculpture, book covers, maps and film posters. Do you want some concrete examples? In 1921 I drew 40 color plates for an edition of One Thousand and One Nights, while the following year I illustrated the book of Persian fairy tales The Book of the Parrot. Furthermore, with my works, I participated in the Great Futurist Exhibition held in Milan in 1919 and in the International Futurist Exhibition in Berlin in 1922.

As for literature, in the magazine “Italia futurista”, between 1916 and 1918, I published numerous articles and stories. In 1917 I took part in an intense debate on the role of women in which I stated my above beliefs in no uncertain terms, reaching the conclusion that our entry into the world of work has made us self-reliant and independent. In short, companions of our men and with whom to build an equal and no longer submissive relationship, because we have all come out of the war changed. I particularly remember one of my articles entitled Le donne del posdomani, also from 1917, in which I invited all of us to keep the temper acquired during the war intact, even for when our men returned from the front.

Returning to the novel starring Giorgina, A woman with three souls from 1918, this has been labeled as proto science fiction. I don’t know if I agree. Certainly through the vicissitudes of my protagonist I wanted to demonstrate to guys like Marinetti, who a short time before had published an offensive text to say the least entitled “Come si seducono le donne”, that a woman is far from being the one-dimensional creature that he believed. But, on the contrary, she is complex and changeable, and capable of assuming very different behaviors and roles in the course of her existence. As evidenced by my story, or should I say the three stories of my life.

And as Art has always demonstrated. After all, in my last essay from 1964, Eterno Mediterraneo, I try to embark on a sort of journey in search of the sources of art.

I don’t know if you will remember me, but to you who read and, in particular to the women among you, I address these heartfelt words: you can become anything you want and Art inspires you in this because true Art, just like us women, has always had the courage to face change, to accept it without hindering it, thus leaving testimony of a past that is impossible to forget and anticipating the future even before it really manifests itself.