by Valentina Biondini, literature expert

The column “Who’s Next?” returns to talk about a brilliant and multifaceted young woman who lived in the last century who, since the posthumous publication of her work, has never ceased to be at the center of exhibitions, books and television broadcasts. Her life was even told in a movie, “Charlotte” by director Frans Weisz in 1981. It is precisely Charlotte Salomon, a Berlin Jewish artist, author of a totally unique and innovative work that challenges the relationship between fiction and reality, as it is already evident in the title: “Life? Or theater? ”, in the original language “Leben? Oder Theater? Ein Singespiel “.

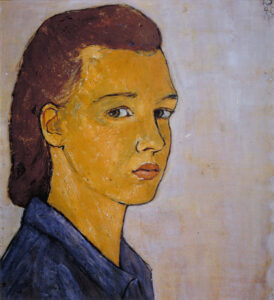

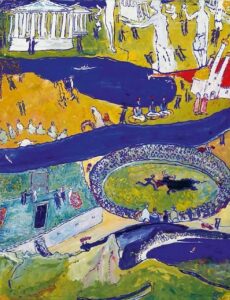

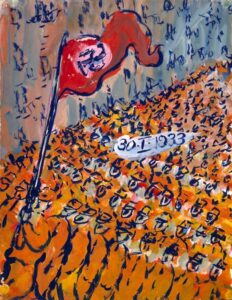

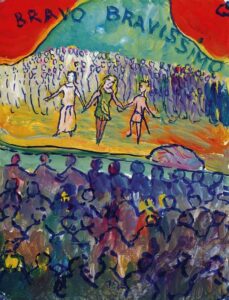

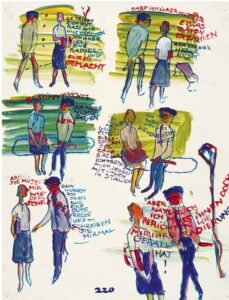

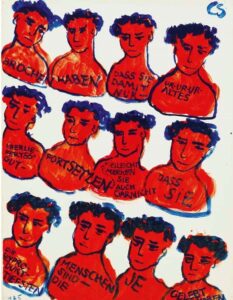

Created over a period of about two years, between 1940 and 1942, during the dark age of the Holocaust, “Life? Or theater? ” is composed, in its final form, of nearly 800 plates made with the “gouache” technique or, to put it in French, gouache. It is a painting technique similar to watercolor in which, however, there is a greater amount of pigment than water. In fact, the artist uses only the three primary colors of red, blue and yellow, while the illustrations are accompanied by her comments in third person. In Salomon’s painting, very personal and capable of passing from detailed descriptions to extreme stylizations, the echoes of German expressionism, the Fauves, Chagall and Modigliani are strongly present. Moreover, although less explicitly, there are references to the Italian Renaissance, including Michelangelo and Titian. Also, the painter had come into contact with these expressive currents during her travels in our country. But what greatly surprises about this young woman is her deep self-awareness, which makes her unmistakable in the general panorama of art.

From a stylistic point of view, in her works painting, philosophical poetry and musical commentary meet. It is no coincidence that this artistic method has been defined by some as an ante litteram graphic novel. It has in fact been noted that each table is consequential to the previous and the next, in a sort of modern frame. In this way the images appear to be part of a play or even a film script. After all, in this distinctive iconography even the word takes on an essential aspect. This is particularly clear in the monologues of the characters, where the expressive solutions adopted manage to totally combine the visual and linguistic planes. So an original compositional synthesis which, drawing on contemporary aesthetics, becomes painting, illustration and storytelling.

However, from the point of view of the content, “Life? Or Theater? ” traces the dramatic history of the author’s family starting from 1913, the year in which her aunt Charlotte, from whom she inherited her name, committed suicide when she was just eighteen. Therefore, it sometimes happens that even history, with the looming tragedy of the Shoah, enters the story. In fact, we find tables that illustrate the arrogant Nazi parades, the unprecedented violence against the persecuted and the terror of the latter. But these ideological elements never prevail over the narration of her private story, which instead turns out to be the true focus of the work.

For this reason, never as in this case, to understand the hidden meaning behind an artistic production, it is a must to be acquainted with the biography of her author. Biography that flowed directly into the work, being the material itself, as the title betrays. Charlotte Salomon was born in Berlin on April 16, 1917 into an upper-class Jewish family. Her father, Albert, is a well-known surgeon and university professor, while her mother, Franziska, is a nurse. Her childhood passed quietly until her mother died when she was only nine years old. It is a suicide, but the tragic truth is hidden from her for a long time. A few years later her father married Paula Lindberg, a famous contralto of Jewish origin. In 1935, with Hitler in power for two years and the racial laws already in force, Charlotte, whose artistic talent has now blossomed, is the only “one hundred percent Jewish” to be admitted to the National School of the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts. This experience allows her to learn the traditional techniques and brings her new affections and friendships. But she is also marked by growing discrimination, such as the exclusion for racial reasons from a competition in which she was given as a favorite. So, after only three years, she is forced to abandon the Academy. On November 9, 1938 in Germany the situation worsened: it was the Night of Broken Glass, the synagogues were attacked, the shops of the Jews destroyed, thirty thousand of them were deported to the concentration camps. Charlotte then decides to take refuge in Villefranche-sur-Mer, in the south of France, with her maternal grandparents who had arrived there five years before to escape the widespread anti-Semitism of Germany.

For this reason, never as in this case, to understand the hidden meaning behind an artistic production, it is a must to be acquainted with the biography of her author. Biography that flowed directly into the work, being the material itself, as the title betrays. Charlotte Salomon was born in Berlin on April 16, 1917 into an upper-class Jewish family. Her father, Albert, is a well-known surgeon and university professor, while her mother, Franziska, is a nurse. Her childhood passed quietly until her mother died when she was only nine years old. It is a suicide, but the tragic truth is hidden from her for a long time. A few years later her father married Paula Lindberg, a famous contralto of Jewish origin. In 1935, with Hitler in power for two years and the racial laws already in force, Charlotte, whose artistic talent has now blossomed, is the only “one hundred percent Jewish” to be admitted to the National School of the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts. This experience allows her to learn the traditional techniques and brings her new affections and friendships. But she is also marked by growing discrimination, such as the exclusion for racial reasons from a competition in which she was given as a favorite. So, after only three years, she is forced to abandon the Academy. On November 9, 1938 in Germany the situation worsened: it was the Night of Broken Glass, the synagogues were attacked, the shops of the Jews destroyed, thirty thousand of them were deported to the concentration camps. Charlotte then decides to take refuge in Villefranche-sur-Mer, in the south of France, with her maternal grandparents who had arrived there five years before to escape the widespread anti-Semitism of Germany.

Shortly after, her grandmother, who had fallen into depression due to the aforementioned tragic events, attempted suicide. The attempt is thwarted for the first time by Charlotte herself. Unfortunately, the woman tries again the following year, in 1940, this time succeeding. It is at this point that the painter discovers the truth about the long death trail that marked the maternal branch of her family. In fact, it emerges that first her aunt Charlotte committed suicide, then her mother, and after her grandmother. This revelation upsets her, especially as she begins to suffer from severe depressive crises. So, to exorcise her inner discomfort and partly the concrete fears represented by the Nazi persecutions, Charlotte starts to work hard on “Life? Or theater?”. The work goes on for about eighteen months among sacrifices of all kinds. In 1943, fearing to be captured by the Nazis and knowing that she had to hide, she entrusts all her writings to her doctor, Dr. Georges Moridis, so that, at least they could be saved. In the same year she marries Alexander Nagler, also a Jewish refugee in France, from whom she was expecting a child, but in October she was captured by the Nazis and deported to Auschwitz where she was probably murdered on the same day of her arrival, on October 10.

From her short biography, which covers only the first 26 years of her life, at least four key figures emerge. First of all, the stepmother Paula Lindberg with whom Charlotte has a conflictual relationship, made up of adoration and jealousy, but who still represents in any case a reference point for her. Then Alfred Wohlfson, a psychotherapist and vocal trainer, who enters her family circle to teach her stepmother his methods. Charlotte falls in love with him. But he instead falls in love with Paula. So this creates a singular triangle which will be fundamental for the emotional, intellectual and artistic development of the young woman. Then there is the figure of the doctor Georges Moridis, who saves Charlotte’s work from destruction and delivers it intact in the safe hands of the fourth and last key figure, that of Ottilie Moore. Moore is a wealthy American benefactress of German descent who, between the 1930s and 1940s, dedicates herself to helping Jews. At first Charlotte’s grandparents find refuge in her house and then the young woman herself. Ottilie becomes friends with the girl and encourages her with her artistic career, helping even materially. At the end of the war she returns the story of Charlotte’s life to the survivors of her family, that is her father and stepmother, who, in turn, deliver it to the Jewish Museum in Amsterdam where it is still kept and where numerous studies and exhibitions have been dedicated to her.

It is known that, since ancient Greece, there has been a lot of talking about the cathartic function of art. And, looking at Charlotte Salomon’s path, it can be said with absolute certainty that she internalized and made this lesson her own, deciding, when she was afraid of losing her mind, to cling to art as an anchor of salvation. In this way she transformed the pain into a muse and her work into her therapy. In fact, through an unprecedented language for the time, Charlotte deals with subjects linked to her emotional and cultural experiences in a continuous stylistic metamorphosis. So, in that short time in which she was allowed to be mistress of her own destiny, she chose not to give up, but to “heal” through art. The undying success of “Life? Or theater?” shows that she made it. With her energetic painting and her tireless creative force she created a unique and incredibly surprising work. From 2019, finally, even Italian readers can approach “Life? Or theater? ”, since Castelvecchi Editore has published the first complete edition in Italian.

It is known that, since ancient Greece, there has been a lot of talking about the cathartic function of art. And, looking at Charlotte Salomon’s path, it can be said with absolute certainty that she internalized and made this lesson her own, deciding, when she was afraid of losing her mind, to cling to art as an anchor of salvation. In this way she transformed the pain into a muse and her work into her therapy. In fact, through an unprecedented language for the time, Charlotte deals with subjects linked to her emotional and cultural experiences in a continuous stylistic metamorphosis. So, in that short time in which she was allowed to be mistress of her own destiny, she chose not to give up, but to “heal” through art. The undying success of “Life? Or theater?” shows that she made it. With her energetic painting and her tireless creative force she created a unique and incredibly surprising work. From 2019, finally, even Italian readers can approach “Life? Or theater? ”, since Castelvecchi Editore has published the first complete edition in Italian.