The canadian photographer Shira Gold creates images that in their scenic isolation try to combine aspects such as stillness and beauty with those of pain and suffering. Drawing to her experiences of woman, daughter and mother, Shira faces the frequently tormented vicissitudes of our existence, by means of acts of exploration, rediscovery and wonder.

Gold, in fact, decided to suspend her artistic path to take care of her sick mother. After the passing of her parent, she got back to the photographic medium in order to understand the pain that she was experiencing, isolating it, decomposing, and representing it through photographic shoots. A way of discovering her emotions, coming back to live the present moment, without taking refuge in the past anymore. From here originates Shock, a deep and introspective journey, turned towards the processing of emotions felt in front of a loss. This is the first of eight series that culminate in the Good Grief work, that consists in images coming from an incessant and personal research on the theme of transition from pain to healing.

Let’s talk with the artist.

Why did you chose photography to express specific emotions?

In a way, I feel that photography chose me. I have always been a very sensitive, open person and when I was really young, I had a chance to take art classes at Arts Umbrella (a visual and performing arts school in Vancouver). After experimenting with a broad range of mediums, it was clear to me that my hands couldn’t express through other art forms the things I felt inside. When I began to experience the magic of capturing fleeting moments in time, rendered through the magic of the darkroom, I was completely transfixed.

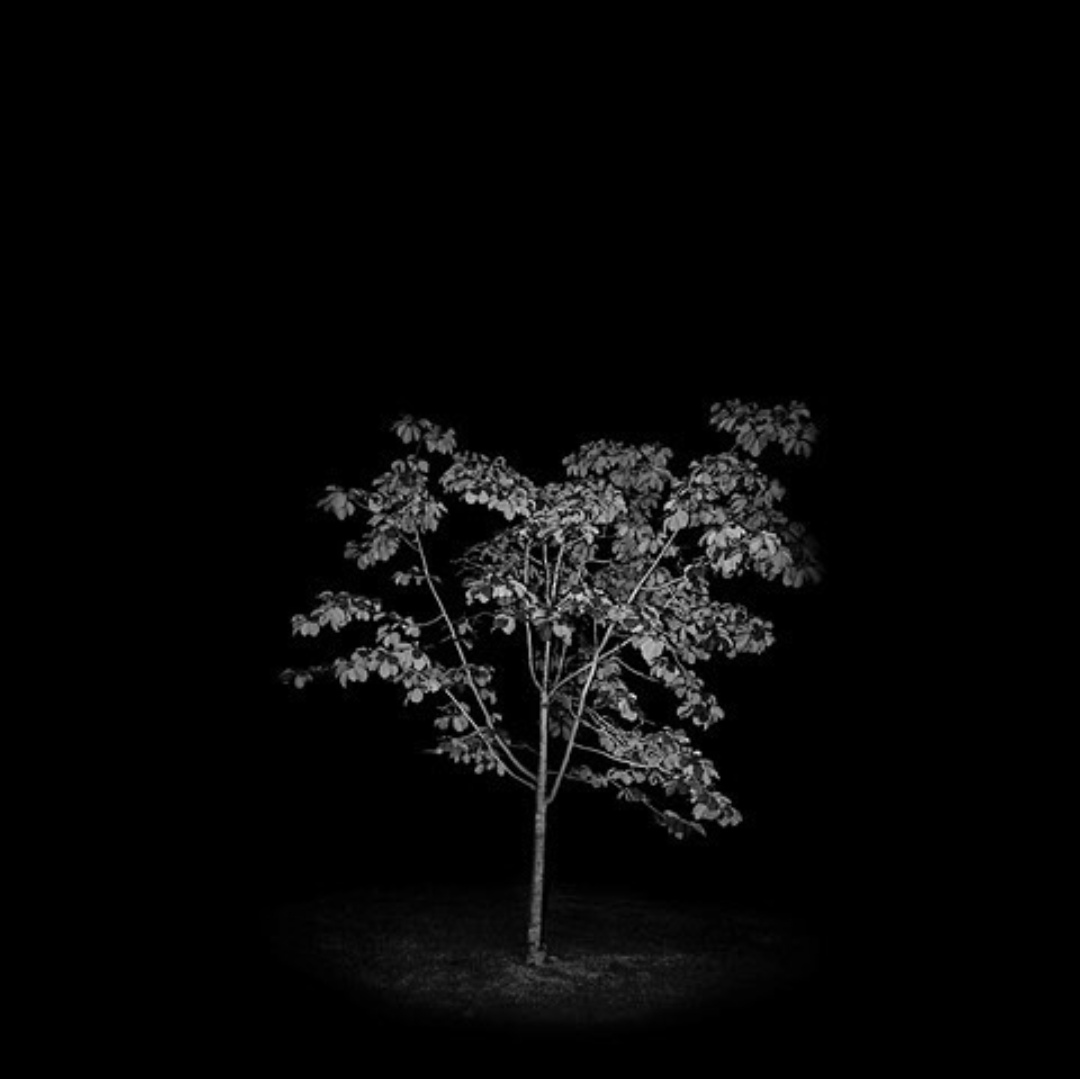

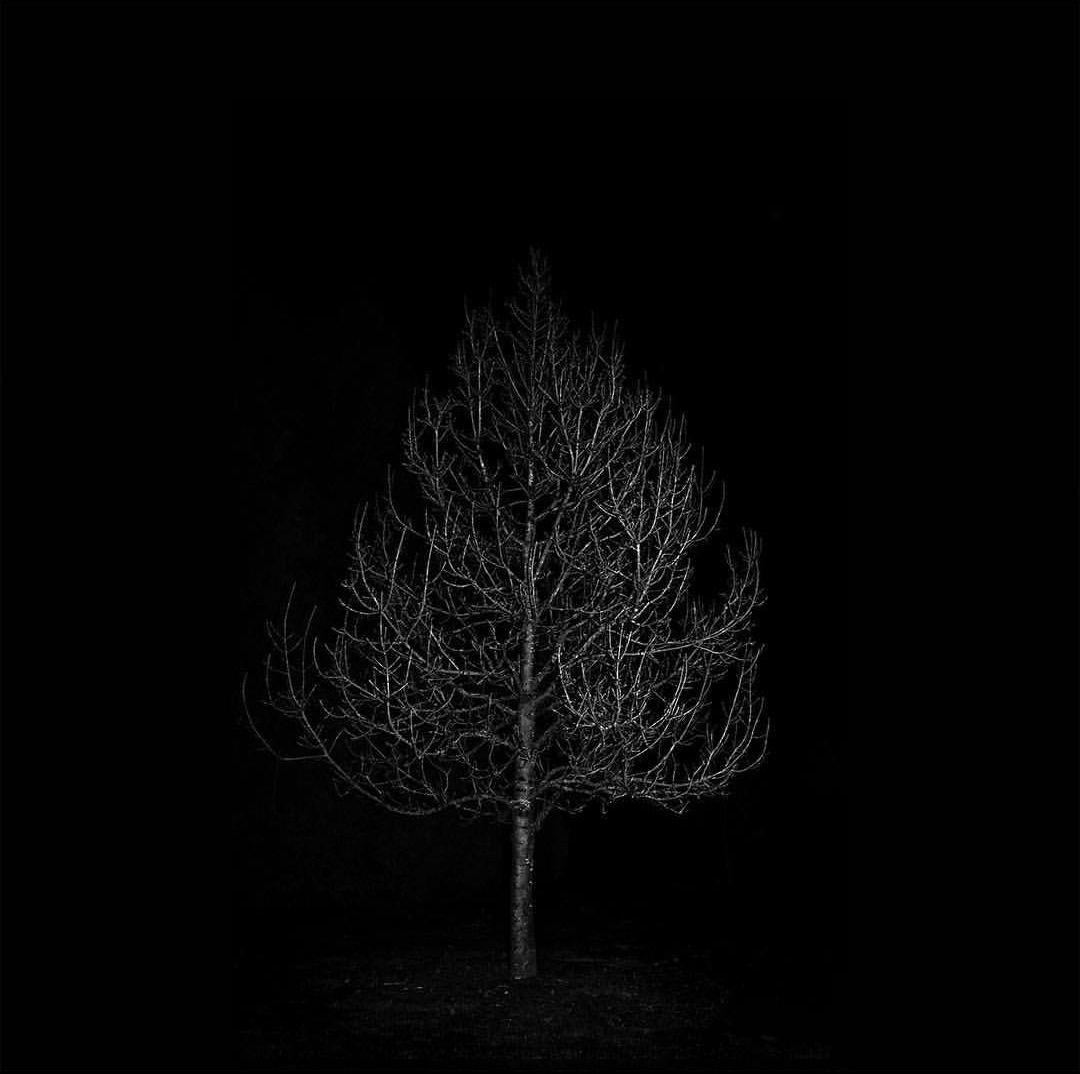

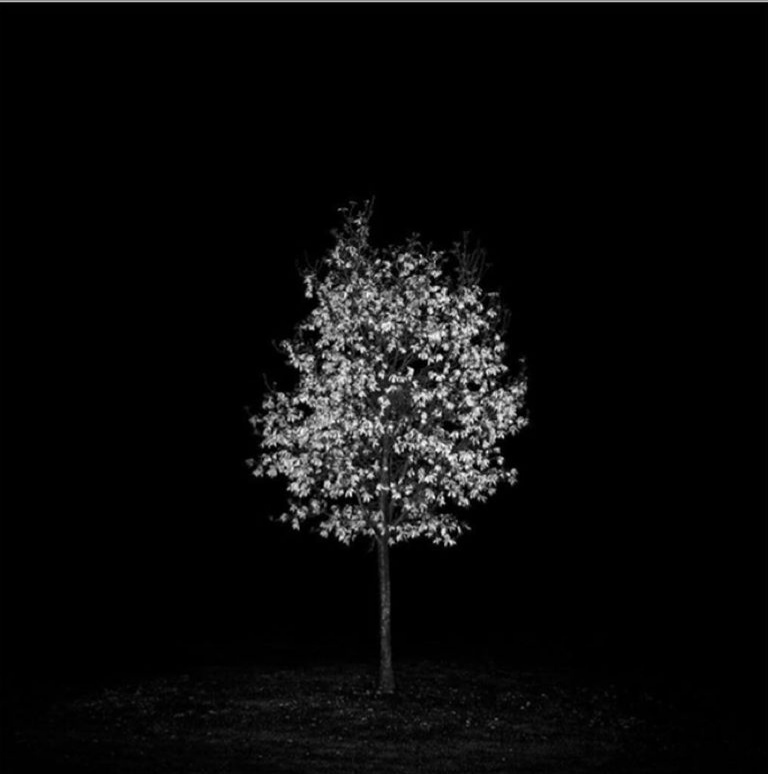

In Shock you seem to explore pain through a black and white universe, almost dark and at times disorienting, where each image situated in the foreground looks like a self-portrait, a consequence of a compassionate inner reality, keen on returning to life. Can you tell us about that?

That is a really wonderful observation. My experience with the early moments of grief was filled with contradictions. I was very disoriented by the pronounced contrast between my acute awareness of the life going on around me and the absolute loss of my mother. I felt trapped by a foreign reality and extreme emotions – I often think of the isolation of that time as though I was living in a terrarium, sequestered in my own grief but also on display in some ways. Well-intentioned people tried to support me but I felt as though I was wearing my private feelings about loss, almost like clothing. So these images are absolutely self-portraits, as are all of the images in Good Grief.

So in your work the natural element becomes a symbol in order to face the complex process leading to the passage of the grief. When did the beauty and the power of nature allow you to transform suffering into rebirth?

I have the great fortune of having been born and raised in Vancouver, Canada. It is a city surrounded by temperate rainforest. Though nature is bountiful here, I think I often took it for granted. It wasn’t until the birth of my children that I actively engaged with it as a part of my routine. When my children were small, my husband worked out of town during the week. It was an overwhelming time. There were small gaps in my day when they were both in school and I could venture into nature as a meditative respite. I began to bring my camera with me, and it became a ritual. In those precious moments there were times when I was so emotionally taken with the landscape that I’d be in tears as I focused on what was in front of my lens. It took some time to understand why. When I did, I realized that what I was seeing was my grief in the landscape. I began to realize that images could articulate my journey for me, in place of words. Seeking, documenting, and expressing my story has been profoundly healing.

Even in the Sea Swept series, you investigate the relationship between inner emotions and external world. In this case the sea, the ocean, is the expression of an internal space. How does the investigation of the moods of our being represent a constant of your artistic research?

Yes, mood is everywhere in the landscape—sometimes the seemingly inanimate world offers a more tangible connection with our inner experiences. When we see images of people, our feelings shape to a specific form, possibly estranged from our own lives. But the abstracted portrait of water can suggest a multitude of emotions, unique to every individual. Its mood can draw empathy and reflection—for me, the world of the sea can be a mirror for my own emotions as well as the infinite possibilities of hope. As a shy and sensitive person, these ocean portraits offer a visual means of expressing the immeasurable depths of the interior self.

Another typical aspect of your images is a sense of stillness and relative calm. Can you tell us about this?

I have a very busy mind. When it isn’t totally active, it seeks stimulation. In many ways, my work contradicts my mind’s behavior. When I create images it is one of the few times I am able to cut out the noise, slow down, and focus. The process is almost medicinal. I seek and capture the stillness that is so elusive and fleeting in my life.

On the contrary, the various series that compose Good Grief all describe the part of a personal and intimate visual process of transformation and change. How these works are connected to each other?

Grief looks different at different points in time, just as our own internal growth does not always reflect the changes on the outside. As a whole, my work traces a journey through grief, with a view to the different landscapes that emerge with the passage of time and distance. They all relate to one another, referencing different emotional stages. Although the aesthetics of each collection within Good Grief are quite different, all of the pieces are connected by an interwoven visual vocabulary, such as the symbolism suggested by nature.

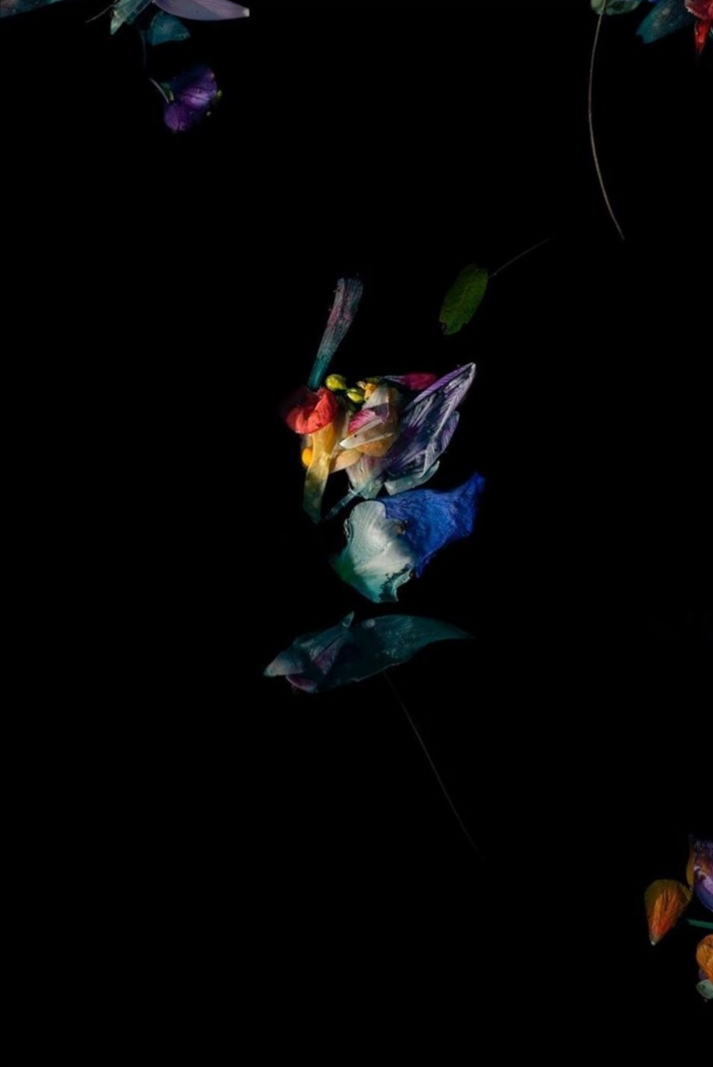

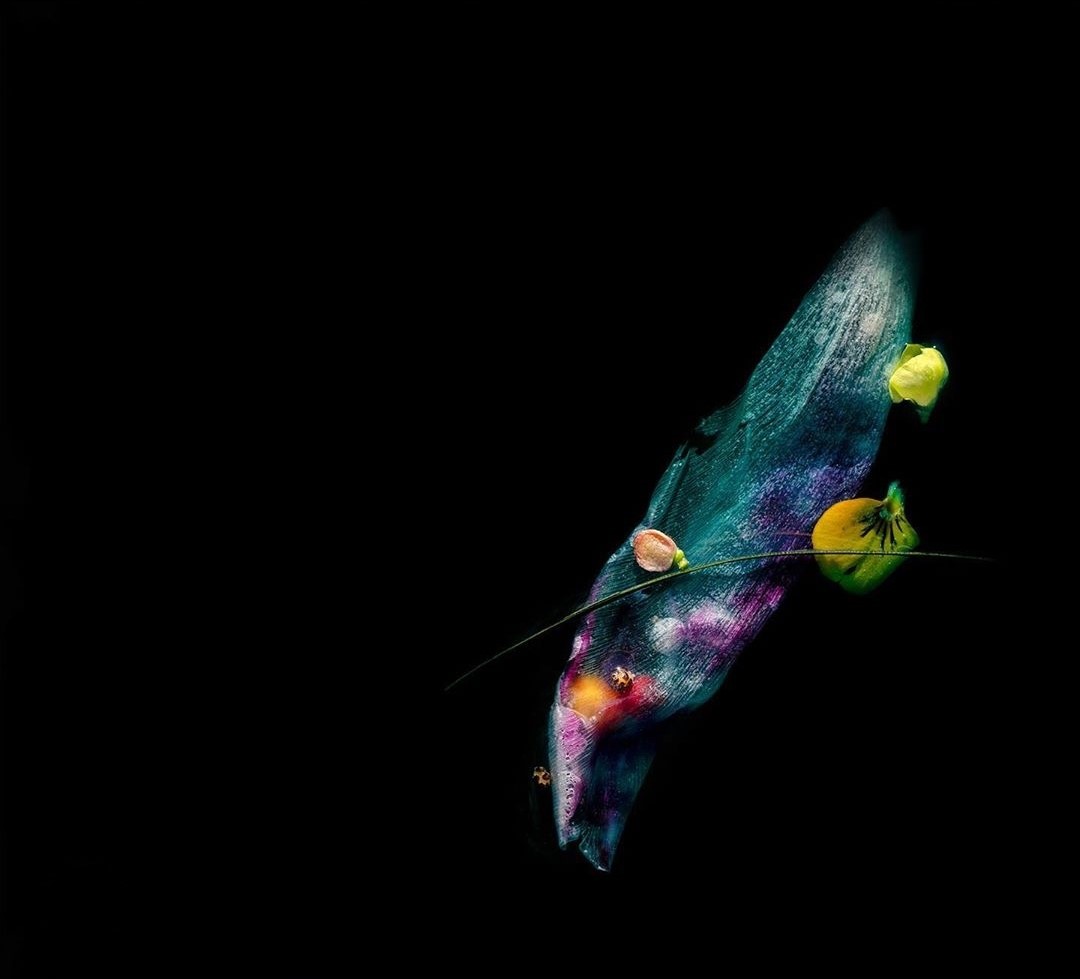

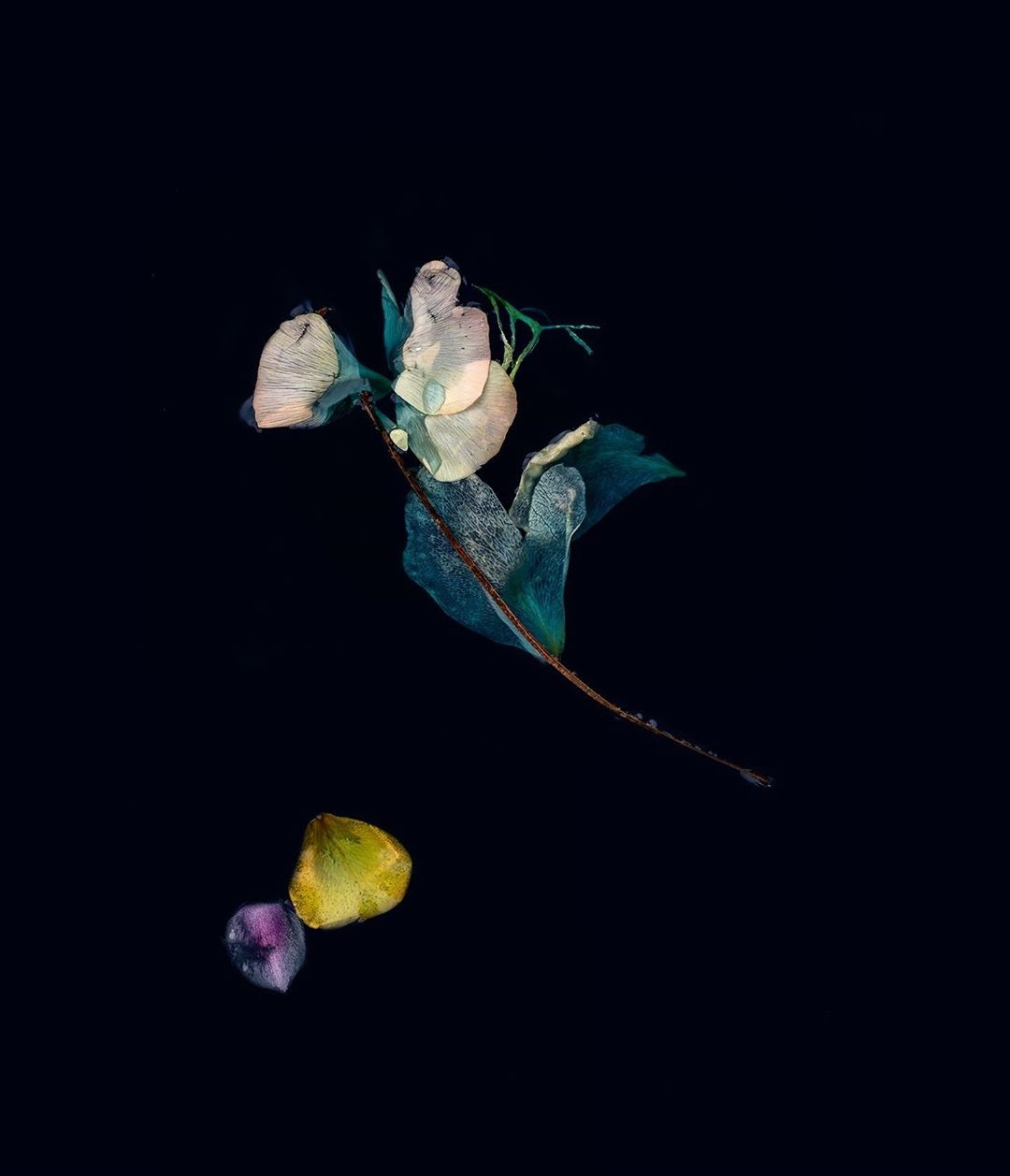

In your last project, The Art of Letting Go, through the images dedicated to the metamorphosis of flowers, you ask yourself about the psychological reasons that lead human being to detach from memories in order to venture in a new context of life, even if it is unknown. What have encouraged you to analyze this subject?

Letting go of the past and making room for the new has always been a challenge for me. I think I realized deep down that I needed to make space in my life for change. Sometimes we hold so tightly to memories in order to feel closer to old realities—even if those memories are beautiful, they can also be painful. But the past is absolute. It felt powerful to recognize that I don’t actually have control over the past, and that it does not have to determine the way I go forward.

Are there some artists or photographers that influenced your work?

The artists who inspire me have not necessarily informed my own aesthetics. Instead, I’m moved and inspired by their work and stories. For instance, I’ve been fascinated by Sally Mann’s work since I was in high school. I truly admire her resolve and bravery, and her view regarding her art was that that everything she ever needed was in her own backyard. The idea that one needn’t seek far-off landscapes to make art really motivated me, especially in the early years with my children, when I couldn’t venture far. I’m also inspired by the great Canadian painter Gordon Smith. And I love the powerful portraits that photographer Carolina Rapezzi captures—documenting important humanitarian and social issues. I also love the satirical commentary that photographer Dina Goldstein uses in her work.

Can you tell us about your next projects?

I am still working on The Fine Art of Letting Go, which keeps evolving. I am also in the early stages of research for a series based on my family’s story of survival during the Holocaust, and my experience as a grandchild of survivors.

Biography: as a photographer, Shira Gold seeks to isolate images of stillness and beauty from complicated and painful moments. Drawing on the relationships as a daughter and a mother, her work explores experiences of grief, embodiment, discovery and wonder. Based in Vancouver, British Columbia, Shira has spent most of her life immersed in fine arts. However, when her mother became seriously ill, she left her career to become her mother’s primary caregiver. When she lost her mother, Shira recognized the need to reclaim her visual voice and returned to her camera soon after becoming a parent. The series Reflect, Transform, Become documents the transformative, complex experience of being a motherless mother, and earned her an Honorable Mention in the 2016 International Photography Awards. Shira’s most recent body of work is entitled Good Grief, a collection of landscape portraits that serve as a visual dissertation of her movements through loss. This work has earned her recognition in many international awards, like the Lensculture Art Photography Award. Shira’s work has been exhibited in several Brick and Mortar galleries in Canada, Italy, Greece, Spain and the United States.

shiragold.com

Instagram: @shiragoldphotography