Written by Valentina Biondini, literature amateur

This time the “Who’s Next?” column is dedicated to a peculiar Italian artist whose artworks developed between the 1960s and 1970s in our country. Then she was consigned to oblivion at least until the early 2000s, when some scholars recovered her memory. We are talking about Ketty La Rocca, whose purpose was giving to art the task of defining the relationship with reality and its knowledge. She had a scratchy, intimate and personal female gaze, but also capable of turning into universal.

This time the “Who’s Next?” column is dedicated to a peculiar Italian artist whose artworks developed between the 1960s and 1970s in our country. Then she was consigned to oblivion at least until the early 2000s, when some scholars recovered her memory. We are talking about Ketty La Rocca, whose purpose was giving to art the task of defining the relationship with reality and its knowledge. She had a scratchy, intimate and personal female gaze, but also capable of turning into universal.

Gaetana La Rocca – Ketty was her nome de plume – was born in La Spezia in 1938 and, after her master’s degree, she moved to Florence where, in order to support herself, she carried out several kind of jobs, for example she was a radiologist and also a teacher. At the beginning of the ‘60s, through her friend Lelio Missoni (aka Camillo), she met Group 70 founded by the artists and activists Miccini and Pignotti and started making art, without going through painting. Gruppo 70 was a movement committed to promoting Visual Poetry in the Florence environment – more secluded than dynamic cities such as Rome, Milan or Turin – whose aim was fighting the new communication and consumption models with artworks that used the same language, made up of writing and images.

Gaetana La Rocca – Ketty was her nome de plume – was born in La Spezia in 1938 and, after her master’s degree, she moved to Florence where, in order to support herself, she carried out several kind of jobs, for example she was a radiologist and also a teacher. At the beginning of the ‘60s, through her friend Lelio Missoni (aka Camillo), she met Group 70 founded by the artists and activists Miccini and Pignotti and started making art, without going through painting. Gruppo 70 was a movement committed to promoting Visual Poetry in the Florence environment – more secluded than dynamic cities such as Rome, Milan or Turin – whose aim was fighting the new communication and consumption models with artworks that used the same language, made up of writing and images.

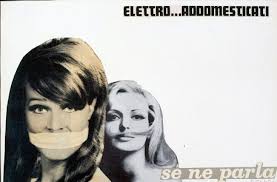

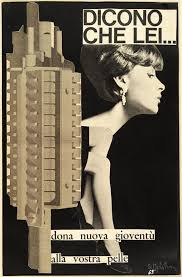

In this first phase, therefore, La Rocca created collages with words and photos taken from newspapers and magazines and combined them with the intention of reversing them semantically. In such a way she meant to reply, with the same weapons, to the bombardment of images and messages originated by mass communication. Her poetic-visual beginnings within Group 70 were undoubtedly the most markedly ideological of all her entire artistic production. In effect, the collages and poetic compositions of this period expressed a feminist and polemical position towards the stereotypes created, publicized and abused by the media. However, at the end of the ‘60s, La Rocca moved away from Group 70 because she gradually left the canons of Visual Poetry.

In this first phase, therefore, La Rocca created collages with words and photos taken from newspapers and magazines and combined them with the intention of reversing them semantically. In such a way she meant to reply, with the same weapons, to the bombardment of images and messages originated by mass communication. Her poetic-visual beginnings within Group 70 were undoubtedly the most markedly ideological of all her entire artistic production. In effect, the collages and poetic compositions of this period expressed a feminist and polemical position towards the stereotypes created, publicized and abused by the media. However, at the end of the ‘60s, La Rocca moved away from Group 70 because she gradually left the canons of Visual Poetry.

Between 1967 and 1969, she embarked on a less controlled and protesting path, aimed at analyzing communication. In other words, she began to look for some kind of truth and authenticity able to go beyond the ambiguity of language and through them she wanted to express her presence in the world. In this phase, the collages were associated with other techniques and performances focused on themes like body and gesture. In the Installazione con J (1970), for example, La Rocca placed large black PVC letters in the daily space, large-sized, similar to those of advertising signs, which surprisingly refer directly to the person. J, in effect, stands for “je”, so “me”. The very feature of these artworks was their semantic misunderstanding: the sentences, detached from the context, offer several kind of interpretations and thus misunderstandings. Here Magritte’s reference, in particular to the Belgian artist’s word games, was markedly evident. Nevertheless, her goal, as the international neo-avantgarde movements, was looking at the present with a critical eye and, using the most popular means of mass society (the billboard, the visual / verbal language of advertising, the objects of the urban furniture etc.), creating images apparently common, but full of an ironic and accusatory meaning.

Between 1967 and 1969, she embarked on a less controlled and protesting path, aimed at analyzing communication. In other words, she began to look for some kind of truth and authenticity able to go beyond the ambiguity of language and through them she wanted to express her presence in the world. In this phase, the collages were associated with other techniques and performances focused on themes like body and gesture. In the Installazione con J (1970), for example, La Rocca placed large black PVC letters in the daily space, large-sized, similar to those of advertising signs, which surprisingly refer directly to the person. J, in effect, stands for “je”, so “me”. The very feature of these artworks was their semantic misunderstanding: the sentences, detached from the context, offer several kind of interpretations and thus misunderstandings. Here Magritte’s reference, in particular to the Belgian artist’s word games, was markedly evident. Nevertheless, her goal, as the international neo-avantgarde movements, was looking at the present with a critical eye and, using the most popular means of mass society (the billboard, the visual / verbal language of advertising, the objects of the urban furniture etc.), creating images apparently common, but full of an ironic and accusatory meaning.

Over time La Rocca noticed more tangible the impossibility of language to be the means of a real and truthful communication, and demonstrated this assumption by composing non-sense texts. The climax was reached in Dal momento in cui qualsiasi (1970), a composition that collected fragments taken from the language of news, politics and bureaucracy. The text was formally correct, but it had no meaning at all. We are in the early 1970s and this no confidence in conventional language led her to the exploration of non-verbal territories. Following in Lévi-Strauss’ thinking, La Rocca started to revalue gesture, meant as a symbol of repressed corporeity against the supremacy of verbal language. A corporeity which has been now enslaved by capital and unable to convey authentic messages (any more metterei now sopra). At this stage she mainly used photography, but together with other experimental forms, such as videos.

Over time La Rocca noticed more tangible the impossibility of language to be the means of a real and truthful communication, and demonstrated this assumption by composing non-sense texts. The climax was reached in Dal momento in cui qualsiasi (1970), a composition that collected fragments taken from the language of news, politics and bureaucracy. The text was formally correct, but it had no meaning at all. We are in the early 1970s and this no confidence in conventional language led her to the exploration of non-verbal territories. Following in Lévi-Strauss’ thinking, La Rocca started to revalue gesture, meant as a symbol of repressed corporeity against the supremacy of verbal language. A corporeity which has been now enslaved by capital and unable to convey authentic messages (any more metterei now sopra). At this stage she mainly used photography, but together with other experimental forms, such as videos.

In 1972, for example, she shot Appendice per una supplica, one of the first videotapes ever produced in Italy. In the video, shot in black and white and with a fixed camera, the artist focused on the gestural language of her hands that she placed in the foreground. The aim was rediscovering a primitive expressive way in the place of word. Based on the same purpose the photobook In principio erat, published twice in 1971 and 1975, where, always looking for authentic forms of communication, the artist focused on the language of gestures (also protagonist of the aforementioned Appendice per una supplica).

In 1972, for example, she shot Appendice per una supplica, one of the first videotapes ever produced in Italy. In the video, shot in black and white and with a fixed camera, the artist focused on the gestural language of her hands that she placed in the foreground. The aim was rediscovering a primitive expressive way in the place of word. Based on the same purpose the photobook In principio erat, published twice in 1971 and 1975, where, always looking for authentic forms of communication, the artist focused on the language of gestures (also protagonist of the aforementioned Appendice per una supplica).

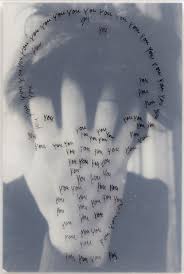

The contest between gesture and word reached its peak in the series Mani con discorso (1973). Here the word became just a sign, while the image a support for calligraphy. The writing was incomprehensible, fragmentary and only the word ‘you’ was repeatedly and fairly readable. The insistence on this word stood for a prayer or a supplication and hid the need for a recognition. In other terms, writing became an affirmation of one’s own identity threatened by the perception of the inexorable transience, an urgency of leaving a trace, but also an attempt to get in touch with the other.

The contest between gesture and word reached its peak in the series Mani con discorso (1973). Here the word became just a sign, while the image a support for calligraphy. The writing was incomprehensible, fragmentary and only the word ‘you’ was repeatedly and fairly readable. The insistence on this word stood for a prayer or a supplication and hid the need for a recognition. In other terms, writing became an affirmation of one’s own identity threatened by the perception of the inexorable transience, an urgency of leaving a trace, but also an attempt to get in touch with the other.

On the other hand photography was the starting point for the last phase of her research, where we find Riduzioni and Craniologie. In Riduzioni, words and images are mutually deleted: the contours of the photos were gradually corroded by a vertical or horizontal sequence and were overwritten by non-sense texts or by the repeated word ‘you’. Writing destroyed the images and vice versa, in a process led by handwriting that enhanced the individual sphere.

On the other hand photography was the starting point for the last phase of her research, where we find Riduzioni and Craniologie. In Riduzioni, words and images are mutually deleted: the contours of the photos were gradually corroded by a vertical or horizontal sequence and were overwritten by non-sense texts or by the repeated word ‘you’. Writing destroyed the images and vice versa, in a process led by handwriting that enhanced the individual sphere.

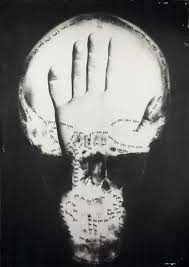

Finally Craniologie, probably her strongest and most felt series because made from X-rays of her own head – in those years the artist had discovered to be affected by a brain cancer. Therefore she used the x-rays of her skull (hence, in fact, the name of Craniologie) as a support for handwriting or for overlapping other photos depicting hands or African masks, in the same style of ancient funeral monuments. Whilst the x-rays represented the visible metaphor of her disease, the artistic manipulation was useful to turn her anxiety into expression and personal memento mori. Furthermore, these dramatically strong and significant pieces of art can be defined as the sum of her research on body, gesture, image and word.

Finally Craniologie, probably her strongest and most felt series because made from X-rays of her own head – in those years the artist had discovered to be affected by a brain cancer. Therefore she used the x-rays of her skull (hence, in fact, the name of Craniologie) as a support for handwriting or for overlapping other photos depicting hands or African masks, in the same style of ancient funeral monuments. Whilst the x-rays represented the visible metaphor of her disease, the artistic manipulation was useful to turn her anxiety into expression and personal memento mori. Furthermore, these dramatically strong and significant pieces of art can be defined as the sum of her research on body, gesture, image and word.

All the passages of her unfortunately too short artistic career – characterized by the contamination between different codes and high and low references, the use of several means of expression have led La Rocca to develop her own personal language which is autonomous and unique still nowadays. In addition, we can affirm that one of her most precious legacies is the idea that art is a means to understand and react to reality by modifying it, without being caught by ideologies, so popular in the years of her times.

All the passages of her unfortunately too short artistic career – characterized by the contamination between different codes and high and low references, the use of several means of expression have led La Rocca to develop her own personal language which is autonomous and unique still nowadays. In addition, we can affirm that one of her most precious legacies is the idea that art is a means to understand and react to reality by modifying it, without being caught by ideologies, so popular in the years of her times.