by Valentina Biondini, literature amateur

Hannah Höch, stage name of Anna Therese Johanne Höch, was born in Gotha, Germany, in 1889. Mainly known for the work she produced during the Weimar Republic, today she is considered one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century Dadaist season and a pioneer in the technique of photomontage. Hannah Höch is in fact the woman who innovated the collage technique, elaborating images taken from different types of magazines, in a continuous cross-reference of political-cultural ideas.

She grew up in a middle-class family and in 1912 she enrolled at the Charlottenburg School of Applied Arts, Berlin, with the desire of becoming a painter. However later, to please her father she chooses to follow the address of graphic arts instead of Fine Arts. Despite this, she decides since the ’10s to manifest her creativity through that apparently disrupted but so eclectic language that is collage. In fact, this technique uses images cut from newspapers, magazines and other kind of illustrations which, combined together, return an emotionally engaging and at the same time sarcastic and biting perspective of the world and reality. A compositional aesthetic that Hoch internalizes thanks to being friend with some great personalities of the artistic field. Among them, Theo Van Doesburg, Kurt Schwitters and Moholy-Nagy. The resulting satire is bitter and strident, and does not spare conflicting themes of public and private life.

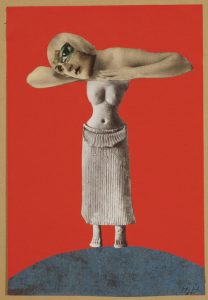

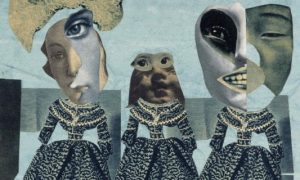

In this regard, we mention works such as “Staatshäupter Heads of State” (1918–1919) and “From an Ethnographic Museum”. These are works from which emerge concepts related to identity and gender, expressed with a sensitivity that recalls the subsequent feminist thinking. In 1915 she began a relationship with Raoul Hausmann, a member of the Dada group in Berlin and two years later, in 1917, she is involved in the group, so that at the first Dada International Fair in 1920, she exhibited nine works. After all, Dadaism is an avant-garde artistic and literary movement and its name comes from the onomatopoeic word “dada” of the children’s language (properly “horse”) found by its creator, Tristan Tzara, opening a French dictionary at random.

Therefore the word “dada” itself does not mean anything. In fact, from its origins this movement was characterized by a “destructive” connotation that tended to make controversy towards politics, mankind, philosophy, art and society. In short, it railed against all forms of institutionalized humanity. For such a movement, which developed following the failure of any ideology, the collage technique was a perfect solution to express unease. In fact with the collages the artists, in addition to alluding with the images fragments to historical and social impulses, try to destabilize the pre-established order, filtering it through a paradoxically sensible and centered non-sense. In reality the only feature that, at least in Germany, made the Dadaist group homologated to the rest of society was the gender imbalance. So, most of the Dada artists were men, and the figure of a woman was an exception within the movement. Therefore Höch’s history highlights how male chauvinism even lodges in the most revolutionary artistic movements. On a closer inspection, there were only about ten Dadaist female artists and most of their work has been unjustly forgotten. Höch herself, despite her skills, faces obstacles to be taken seriously by the movement. The group even hardly accepts, and then thinks about it, her participation to the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920, an important inaugural showcase for the movement. Despite this, the artist managed to emerge thanks to her talent and iron determination, proving herself capable of contrasting chauvinistic creations through a more modern and stimulating perspective.

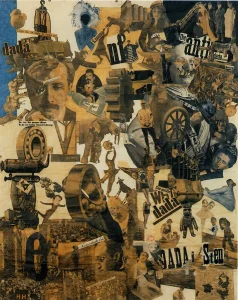

The kaleidoscopic visions in her montages show us German society and culture between the two wars through a feminist, extravagant, almost ambiguous gaze. Furthermore, her works of art are charged with a sharp social criticism of the Weimar Republic. One of her earliest and most famous works is “Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany” (1919). The collage, in poster format, superimposes such different and variegated images, so much so that the same composition, on a first analysis, is chaotic and destabilizing. In reality, looking closer, two groups of images emerge distinctly: those of people and those of machines. A conceptual dichotomy that on one hand alludes to the conflict between man and machines. On the other hand it underlines how lively German society feels the need for an indispensable industrialization to get out of the world conflict. Another interesting element of this work is the map of Europe placed in the lower right corner where, according to some, are highlighted the countries that had granted women the right to vote. After all, we must say that, although Weimar Republic decreased gender differences, among other things by granting suffrage to women in 1918, legal rights and political participation remained limited. Furthermore, women could access the labour market but they had to accept low-paid jobs and carry out well all the other activities at home and regarding the family at the same time.

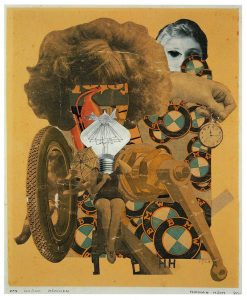

And Hannah Höch was the woman/artist who represented this gender discrimination in an innovative way. For example a montage such as “The Beautiful Girl” (1920), depicts a woman who, while working, has a light bulb in place of her head and on each side, a car tire and a lever blocking her. Here Höch uses clippings from women’s magazines and other media to highlight the contradictions and complexity of women’s roles. The work, in fact, shows how much women’s social positions explored at the time, not just in terms of law and work, but also in terms of sexuality and female identity. However, women’s reality and daily life was often in contradiction with the ideals and expectations that were required. Höch therefore wanted the viewer to be disturbed by traditional concepts of gender, presenting conflicting ideas of femininity and, why not, masculinity. And this is achieved through repetitive and symbolic elements, such as the oval wheel or the clock.

In this way she manages to subvert the seductive intent of the advertising images she uses. Indeed, the colors appear flat more than attractive, the decapitated female figure is reconstructed as if it was merchandise, while a figure behind stares at her with disembodied eyes. It is as if not only the autonomy of women is denied, but that of humanity itself, bewitched by a corrosive modernism. On the contrary, Hoch’s freedom seems to be reflected both in her artistic practice and in her private life. In 1922 she left Hausmann and, four years later, began a relationship with another woman, the Dutch writer Til Brugman and she lived with her in The Hague from 1929 to 1935. These are details that make her a cosmopolitan and emancipated woman for her time. After the end of the relationship with Brugman, the artist marries a young pianist named Kurt Mattheis. During the 1930s, with the advent of Nazism, Höch, unlike many of her artist friends, refuses to leave the country and retreats to a villa outside Berlin trying to keep a low profile, aware that a person like her is certainly disliked by the regime. In addition, the Nazis close the Bauhaus in Dessau before Höch can exhibit at her solo exhibition, scheduled for 1932.

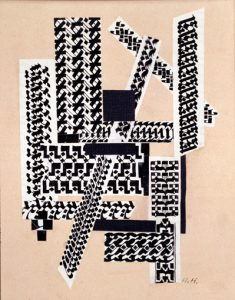

Removed from the world art scene, censored by the Nazis for being “degenerate”, Hannah nevertheless continues to work and develops a completely new style that, from the second post-war period onwards, clearly moves towards abstractionism. Mainly she exhibits abroad and in the meantime refines the photomontage technique, continuously exploring its potential. In addition to this, she creates the archive of the Dadaist’s works, which will make it possible to rediscover the group’s work after the Second World War. In 1945, after the war was over, she resumed exhibiting internationally, and she would continue for the rest of her life. However her work only gained great interest after the major exhibition held at the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts in 1971. Another very important retrospective is in 1976, at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and at the Nationalgalerie in Berlin. After her death in 1978, her complex work is carefully analyzed and deepened. The artist is credited with understanding the complicated and close relationship between art and politics, creating works that go beyond technical innovation, which is nevertheless present.

The fact that Höch has been a pioneer both in her art field and in highlighting an innovative female perspective, despite the injustices of a male-dominated culture, reflects her talent and determination. To this day, her art continues to integrate perfectly into that contemporary reality made up of manipulated and reconstructed digital images. But at the same time it gives us back that critical spirit that still manages to make us reflect and amaze us.