by Romina Ciulli e Carole Dazzi

Can photography have such a figurative ability to tell the temporality of existence? Greg Sand, an American artist/photographer who uses found photographs with the aim to explore concepts like memory, absence, loss and death, seems to feel the need to answer to this question. In fact, in his works these themes emerge through a manipulation of images that gives back an almost surreal connection between the existing figure depicted in the photo and the consequent inescapable vacuum to which it is destined.

Actually what Sand tries to question is the traditional role of “object” photography, or rather its conceptual nature to define reality. This personal research is carried out using digital technologies and artistic practices such as collage, with which the artist is able to explore the fragmentation and impermanance of images and their content by means of a continuous coming and going between past and future, presence and absence. It follows a sensation of perturbation, disorientation, an almost melancholic reflection on how photography, although has the power to immortalize seemingly an endless moment, actually reveals itself as fleeting as life. Many of his works, from Echoes to Chronicle, from Absence until Remnants (just to mention some of them) emphasis this kind of conflicting truth that derives from the lucid decomposition of reality and memory. Let’s talk about this with the artist.

In your projects you use photography as a means to examine themes connected with to memory, loss, absence and death. What emerges is a melancholic atmosphere, nearly surreal, where the figurative image and the concept of fugacity of the humane nature produce a sort of perceptual disorientation, but in some way especially emotional. How would you describe your work?

I describe my work as conceptual with a hint of surrealism. I consider it to be subtle and quiet with both a somber and nostalgic tone. My work is almost always an effort to work through the themes you mentioned: memory, loss, absence, and death. It is often an attempt to reconcile the reality presented inside of a photograph with the reality that exists outside of that photograph.

Ancient portraits, ferrotypes, snap-shots, photo booth strips, use of juxtaposition, collage, stereoscope, collodion: where do you pick up the material for your projects and how do you plan your artistic process?

I mostly find the materials for my work from eBay, antique stores, and flea markets. Inspiration frequently comes from the found photographs themselves. The feelings of melancholy and disorientation they produce in me often drive my work. An idea for a new approach or a new project can come simply from looking through my found photograph collection.

So your projects are characterized by the use of found photographic material, that each time is blended, modified or combined. In this way the traditional definition of photography, usually linked to the notion of truth, is passed and the reality seems to blur and reveal in the encounter between past and future, time and death. How much can the photographic medium and new technologies affect the experimentation of new artistic paths? And how much do they affect yours?

Photography has long been considered a direct and unmediated representation of the truth. (Although, this is less true in today’s digital world.) I use this notion of truth in my work as a starting point. A photo may show a graduating class from the 1920s. The truth presented in the photo is that these young people are alive and full of potential with their whole lives ahead of them. However, in reality everyone in the photo is dead or close to death. It is these conflicting truths that interest me. I’m not sure when it started, but the nature of reality, including time and death, was something that was often on my mind long before I decided to enter the field of photography. I think it has something to do with my introverted and contemplative nature.

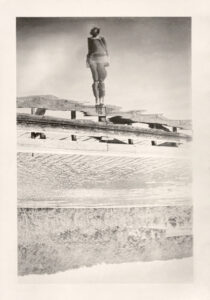

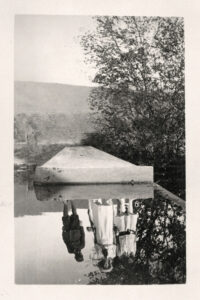

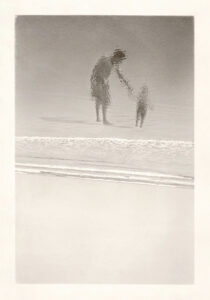

In Echoes you use the contrast to underline how memory could be imperfect, distorted: the water becomes the sky and the human figure relives in the distorted reflection of itself. Which sensations do you try to cause throught this reversed of approach?

Echoes explores the struggle to retain a lucid remembrance of lost loved ones. This series uses found photographs of people next to water in which the figures have been removed and the images have been inverted. The subject becomes the reflection of the subject; the physical becomes the spiritual; the sky becomes the water. What remains is an imperfect, distorted, and elusive memory. I think the reflections in the water serve as a metaphor for reflections on loss. I also consider it a symbol for life, transformation, and change of state.

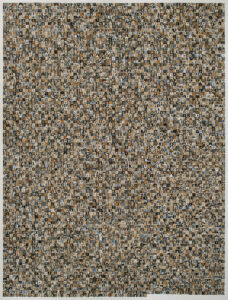

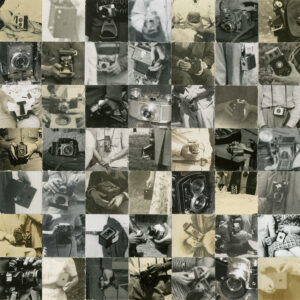

Instead in Chronicle, one of your most representative works, you explore the cognitive and fragmented processes of memory. Memories, in fact, are evoked through details of gestures, hands, faces, flowers, shoes and draperies. Can you tell us about this project?

This series started as an exploration of the overwhelming scope of humanity and human history and the insignificance of the individual. I wanted to find a visual representation of the approximately 6,393 deaths that occur every hour in the world. I chose found photographs because they expose the temporality of life, and I started gathering the photos to collect the 6,393 faces required to make the piece Chronicle: Passing (6,393 Per Hour). As I sorted through my giant assortment of photos, I noticed other elements (hands, feet, shadows) that I thought would be interesting in this format. These subjects still explore the theme of mortality and loss but become even more about the nature of memory and time. I felt it was important to use analog collage, as opposed to digital, to present each antique photograph as a physical object. This emphasizes the effects of time – scratches, fading, discoloration – on the surface, as well as the unique tactile quality of each fragment. I was intrigued by the interactions of the various textures, values, and colors that developed. I found my eye bouncing around from light to dark, from matte to glossy, from bright to dull, from textured to smooth. The pieces became like pixelated masses from a distance that required getting very close to discover each image individually.

Another recurring theme in your artistic process is that of absence (mentioning among others, works such as Once Removed, Absence, Vestige, Traces, Memento). This concept is rendered through the digital removal of the subject or its insubstantial reflection. How this forced procedure of photography manages to preserve the experience of loss and highlighting the conflicted notion of reality?

“By giving me the absolute past of the pose… the photograph tells me death in the future… I shudder over a catastrophe which has already occurred.” These words from Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida precisely describe how I feel when I consider a photograph so old that the subject must be dead. My response has a number of layers: I feel an immediate connection to the living person in the photograph, followed by a dread of what inevitably is to come for them, completed by a sense of grief over what has, of course, already transpired. The removal of the subject – who is very much alive in the photograph – forces the photograph to more truthfully depict a present reality in which the subject no longer lives. The absence left where the subject once stood also reminds the viewer of the loss that has already occurred.

Let’s talk about Remnants, a series in which three different types of pictures, taken at different times, are cropped and combined, generating an assembled portrait, an unicum, for each of the individuals depicted, now dead. This procedure seems to put together the pieces of memory in order to recall the entire existence of every single person. As if semantically “part” and “whole” were two mirror concepts. Can you tell us about it?

I came up with the idea for Remnants while thinking about the way that the moments from our lives are woven together to form our overall memory. I wanted to attempt to physically represent these moments and actually weave them together. I decided that mental images of loved ones are among the most powerful visual memories, so I tried to create likenesses of deceased individuals that–rather than depicting accurate visual representations of the people at any given time–presented a recollected coalescence of their appearances throughout their lives. The most challenging part of this series was finding three photographs of the same person from different points in time that were close enough to the same angle. It required a lot of searching through family photos. Once I had the right images, I scanned them, made prints in which the faces were the same size, cut them into strips, and wove the strips together. The title Remnants references leftover pieces of cloth because this series uses cloth as a metaphor for memory. As Peter Stallybrass writes in Worn Worlds, “The magic of cloth is that it receives us: receives our smells, our sweat, our shape even.” This is one of the marvels of memory as well: we perceive each moment in our lives; these are eventually woven together to form our memory.

In your statement you quote Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida. How much this text and its author have influenced you? And are there other artists or theoreticians you draw inspiration from?

I was exploring the themes of absence and loss before I discovered Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, but he perfectly describes the emotional impact old photographs have on me. This book helps me to understand why I am so drawn to working with found photography and to communicate the intentions of my work. Duane Michals, Disfarmer, Joseph Cornell, M.C. Escher, René Magritte, Susan Bryant, and Billy Renkl are a few of my other influences.

What are your future projects?

I am currently working on pieces that are similar in approach to my Chronicle series. I am being a little looser on these pieces, experimenting with color found photography and the size, shape, and arrangement of the grid elements. I am also working on a series of collages made from postcards and postage stamps. It is a bit of a departure for me in that it is more about aesthetic beauty and is less somber than most of my work.

Biography: Greg Sand is an artist who explores the issues of time and death. He produces work that addresses the nature of photography and its role in defining reality. Sand received his BFA in Photography from Austin Peay State University in 2008. He has received recognition from many jurors, including Chicago art dealer Catherine Edelman, Guggenheim Assistant Curator Ylinka Barotto, and acclaimed artists Shana and Robert ParkeHarrison. Sand currently produces work in Clarksville, Tennessee, and exhibits across the United States.